The Chinese Camellia (Camellia Sinensis), better simply known as Tea, is a plant species which its leaves and young buds are used as the most consumed beverage in the world. Its cultivation and trade had been an economic and political catalyst in Eastern Eurasia for centuries, while its usage gave comfort to generations of weary pilgrims, doleful poets and anxious carpet dealers.

Regardless of popular legends rewvolving idle emperors and romantic princesses loafing under Camellia trees, (I’ve tried steeping fresh leaves, it doesn’t work), Tea usage probably started before 1000 BC, when exact dating is uncertain. Initially cultivated in southern west China, in what is today’s provinces of Sichuan, Yunnan, and Guizhou, as demonstrated by the presence of wild C. Sinensis populations in this region, tea was first used for ceremonial and later for medicinal purposes. As a common beverage, tea drinking only spread after the collapse of the Han dynasty (206 BC–220 AD), becoming an important commercial product during the Song dynasty (960–1279AD).

Given its unique chemical profile, the fresh leaves of the Camellia plant can be modified through a fairly simple manipulation which usually includes steaming, oxidation, and final toasting. The oxidation process give rise to certain chemical compounds, (mostly phenolics such as Catechins, Theaflavins and Flavonoids) which gives the different teas a wide and yet distinct range of flavors and aromas. From white and green teas, through the different Wu longs to your favorite brand of Darjeeling or Assam, this entire selection comes from the same humble plant.

As far as the Tibetan plateau is concerned, the arrival of the divine beverage probably brought an end to the Tibetan compulsion of drinking Yak butter dissolved in hot water and brought forth the joyful blessing of consuming dissolved Yak butter flavored tea.

The tradition attribute this introduction to a Tang dynasty princess named Wénchéng, who brought it with her to Lahsa, following her forced marriage to Songtsän Gampo, founder of the formidable Tibetan empire.

Songtsän (R.605-649), spend the first years of his reign in fierce unification of the Tibetan plateau, eventually turning on China itself, which typically reacted by sending gifts, including one imperial niece. It is said that her dowry included a few bundles of tea, which was happily adopted by the Tibetan elite ever since.

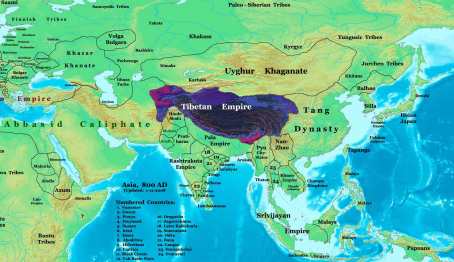

The imperial expansion continued with Songtsän’s successors, pushing the imperial borders on China’s expense all the way to the Hexi corridor and Tarim basin, and well into Central Asia, where a governor was even appointed in Kabul. For two centuries the Tibetans struggled for domination of the region, competing with both the Tangs of China and the Abbasid caliphate, a struggle that lasted until the 9th century’s disintegration of central Tibetan power.

The 7th century had known a considerable increase of trade between China and Tibet, when in accord with the common pattern; China supplied its neighbor with textiles, luxury items and ever increasing amounts of tea, which became a staple among the local population. In return Tibet had supplied the Tang court with the one thing China was never manage to produce, in quantity, nor in quality, horses.

From the dawn of Chinese civilization, this extravagantly rich and fertile sedentary culture was suffering from relative inferiority in front of foreign invaders. Its sheer size and immense population usually kept it safe from permanent occupation, (although historically around half a dozen Chinese dynasties actually were foreign), but brought China under an ongoing payroll in order to pacify its borders, usually with limited success. China’s inferiority in the battlefield was primarily due to her inability to master the equestrian arts which gave its nomadic foes such an advantage, and mostly the mounted archery.

China’s attempts to adapt its army to the age of bow and saddle had stumbled upon a major difficulty, since the Chinese soil lacks selenium which is crucial for the healthy breeding of horses, which again forced her to trade with her outside enemies in order to acquire the indispensable mounts. The Tibetan horses are not a prime catch, especially in compare with the legendary horses of Nisea, Farghana or even the small but tough Mongol horses, however drastic times take drastic measures, and China made an effort to buy war horses wherever she can. From the seventh century onwards, Tibet had exported to China an increasing number of horses, and in return she received Tea, loads of it.

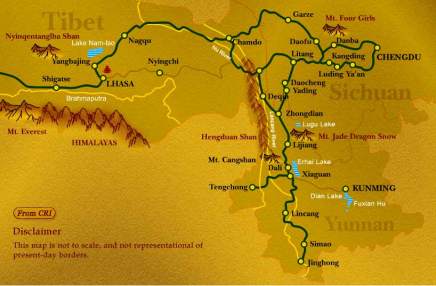

During the Tang heydays the main trade took through a northern route (The so called old Tang trade road) Tángfāngǔdào 唐蕃古道), starting in the historical region of Guānzhōng, or today’s Shǎnxī, then winding through Gānsù, Qīnghǎi, passing the Jīnshā river in northeast Sìchuān, before ascending to the Tibetan lands of Qamdo, Nagqu and ending in Lhasa.

During the five dynasty and early Song periods, there was a steady increase of demand for both Chinese tea in Tibet as well as for horses on the Chinese side, and a testimony for this trend is brought by an 11th century official, stating that “The Westerners have begun to bring good horses to the frontier. All they desire is tea”

. In order to tax and regulate the exchange of goods between the two cultures an official office was established by the Song administration, known as the tea-horse bureau (Chámǎsī 茶马司).

It was in this period when the route we know today was established, when one branch starts from southern Yúnnán, in the tea producing regions of Xīshuāngbǎnnà and Pǔ’ěr. Before heading north through Lìjiāng, Zhōngdiàn (today’s Shangrila) and Lǐtáng. In the Tibetan town of Lǐtáng the road was joined by the northern route, starting from Yǎ’ān, another important tea growing region, as well as a major commercial hub. From Lǐtáng the road pressed on up the Héngduàn mountains and through the vast Tibetan plateau, all the way to Lhasa and further to Nepal and India.

This description is off course an over simplifying one, as same as the better-known “Silk Road” to the north, the “Tea- Horse Road” (Chá mǎ dào 茶马道) is a late 20th century conceptualization of a lucid network of steep routs and mist covered paths, and as other coined terms such as the Musk Road leading from Tibet to Central Asia, European Amber Road and even the maritime Silk road along the shores of the Indian ocean, are all later definitions of long lasting cross-cultural exchange systems, ever changing according to political, economic and ecological conditions.

Tea is a relatively sensitive product, as an organic material it is sesetive to the harms of bad storage, extreme weather changes, and packaging in tea-bags.

The tea that was commonly exported to Tibet was usually produced from a sub-specie of the Chinese Camellia, known as “Big leaved Tea” (Camellia sinensis var. assamica) which still grows in its natural form in the mist covered slopes of Yunnan and northern east India.

The processing manner of the exported tea came as an outcome of the need to transport it in bulks up the mountainous routes, sometimes through towering passes of five thousands meters and more. In order to ensure its safe arrival, the tea was dried and pressed into molds of various shapes, than wrapped and packed before being dispatched up the mountain trails.

This compact tea is known today in China as Pǔěr tea (普洱茶), and classified into two categories, “Shēng” (生茶) meaning, live, or raw, and “Shú” (熟茶) which means ripe, or cooked.

Originally the pressed tea all belonged to the “Shēng” category, which is green or lightly oxidized tea, which by the influence of time and climate underwent through additional oxidation, and slowly aged while receiving a much darker colour, deeper tones and aromas and a much heavier and somewhat sweetish flavor.

On normal terms, it is recommended to consume tea up to two or three years from its production, Shēng Pu’er is the only tea that improves with age, arriving its prime when aged ten years or more, in condition it is stored properly.

The growing demand for Pu’er tea had resulted in the 1973 invention of a bacterial process that managed to produce a somewhat similar result in a considerably shorter time, and the result, the so called “Shú” Pu’er is fairly close to genuine aged Shēng Pu’er.

It is interesting to mention that a few years back China had known a “Pu’er bubble”, when analysts have speculated a dramatic increase of value in the Shēng Pu’er market, which resulted in frenzy investments in Pu’er “cakes” in order to harvest future profits. Nonetheless it is seem today that these speculations where highly exaggerated and this trend had died off since.

没有翻不过的山,没有不能征服的路

“There is no unclimbable mountain, nor path that could not be conquered” -A Tea-Horse Road proverb.

I met Jashi by the concrete cladded banks of the Jin river in Chengdu, Sichuan. After a few paper cups of sugarcane juice and few more pots of tea in a local western style coffee shop with him and his wife Chen, I was thrilled to find out the Jashi was no stranger to the mountain paths of Yunnan, and despite its commercial decline in the last few generations, was indeed fragmented, but otherwise fairly active till the recent years, enabling highland communities access to basic commodities such as salt, spices, medicine and of course, tea.

After a few days we sat in a flourishing apple grove, where Jashi was kindly willing to answer my questions. .

By Jashi’s own definition, The Tea-horse road is a commercial, cultural, and communication network, economically based on Tea and other products and on horses or mules as its mean of transportation (Although footed porters were common in the past) . This rough highland routes network connects different ethnic groups and communities along the fringes of the Tibetan plateau and Himalayas, all united and dependent on one another in order to acquire everyday essentials .Tea had been a crucial part of the Tibetan diet at least for the last one thousand years, used to warm up the long cold winters, as well as a digestive when combined with the grain and meat based Tibetan diet.

Jashi joined the route in his youth, like many before him, the need to make a living pushed him to join the caravans linking the remote towns and villages doting the fringes if the great Tibetan plateau, but also the desire to harden his character and develop manly skills.

According to Jashi, such a caravan was organized either by local business owners who commissioned a party to deliver needed commodities, but most often was assembled by individuals who sought profit by trade.

Such an individual, a route leader oddly nick-named “Mǎ guō tóu” (Horse -pot- head) had to prove himself capable of recruiting the right men and a sufficient amount of pack animals, when such a party would sometimes include around fifty men, and doubled in mounts. En route the leader’s part was to manage the daily routine, locate the suitable routs and camping grounds, and to be able to upper hand any unexpected incidents along the trail.

One such incident, which also demonstrate the special relationship between men of the Tea Road and their horses, occurred when one of the pack horses named Dzero (“grassland eagle”) had slide and fell off a cliff down to the river below, and perished.

With no hesitation, a party had descended down along the cliff side through a perilous path in order to find the horse’s body. After the corpse was found the men have build a wooden platform. Adorned with wild flowers, the deceased comrade was then laid on the platform, while prayers and mourning songs were chanted in his honor.

“Oh my comrade,

You will always remain with me on the route,

But you leave me here, and going to heaven,

While I endure the hardships of life”.

Jashi say that hearing this, tears went down the dead horse eyes.

He explain that horse and men share an intimate bond, a real companionship and mutual dependency, a horse and his owner genuinely understand each other, and just like humans, horses have emotions and are able to smile and cry.

Despite the historical decline of the Tea-Horse Road, commercial traffic on the ancient routes connecting Yunnan, Sichuan, Tibet and Nepal lasted at least until 2006, with the opening of the new Lhasa rail road, it was this year when the Chinese government decided one-sidedly there is no more need for this outdated mean of transportation and initiated a last trade party to commemorate the history, and the end of the Tea horse road. Partly financed by the government and partly by local tea shop owners the profits were used to construct seventeen schools in villages along the road. Despite the official abolition of the road, some regions are naturally too remote to use the new Chinese build transportation networks, and cars, motorbikes, and even horses are still being used to connect these isolated regions.

Since the early 1990’s, there is a growing interest revolving the old tea horse road. With the combined effort of scholars, local businessmen and officials, the old road network is now more popular than ever, among local tourists as well as internationals. This development had help reshaping Yunnan’s image, from a remote and marginalized part of China into a center of ancient international trade and cultural exchange. This process offers many possibilities as well as considerable threats for local communities and environment. The constant growth of visitors (Over five million overseas tourists in 2013,), might possess a real threat for both local communities, becoming over dependent on tourism, and equally for the region’s natural resources and biodiversity. The coming years will be decisive for whether this land of tea and mists will preserve some of its unique historical, environmental and cultural heritage, or fall into over development as many other part of China before it.

Only time will tell if this land of clouds will keep some of its hundreds of years old charm, and its aromas of mountain mist, the lush grove, and the tea leaf.

A former caravan inn (Mǎ guǎn 马馆). Will probably be turned into a boutique hotel, or worst, demolished. Old Lijiang. 2014.

.