Xinjiang, otherwise named Eastern or Chinese Turkestan, has known throughout its long human history frequent shifts of populations, languages and religions, all leaving their mark among its yellow sands and red cliffs. Being one of the only possible routes linking China proper and the western lands, it had been an important cultural junction between the two regions from a fairly early stage.

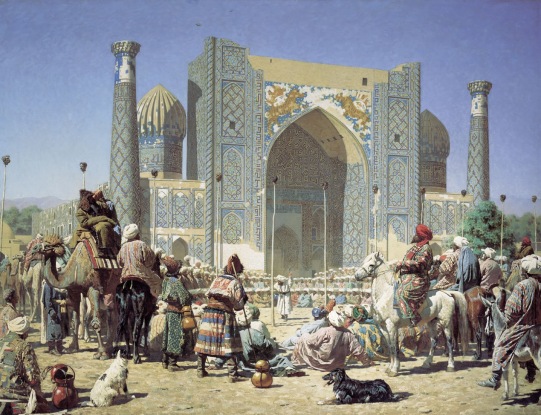

The establishment of the first direct contacts between the Chinese Han court, the kingdoms of Transoxania and the later Kushan Empire, around the first century AD, had fostered what is modernly known as the Great silk road, starching from China`s agricultural heartland through the mountains, river valleys and arid plains of Central Asia and the ancient cities of Iran, eventually linking to the Mediterranean trade centers of the Roman empire.

A false image of the Silk Road will be that of a huge camel train, departing Chinese Xian while pressing through the gigantic Eurasian landmass, eventually halting in some Roman town to unload its heavy burdens of silks, jades, tea and rare spices while exotic maidens in transparent garments sprinkle the camels with rose water and feeding them with peacock meat Shish kebabs.

The Silk Road, perhaps more properly addressed as the silk routs, is an abstract term for a complex and often changing network of routs and paths, linking different cultural and ecological zones while usually delivering a much more trivial selection of commodities. Grains, simple textiles, herbs and medicines, dyes and dried fruits were delivered from the agricultural centers over relatively short distances, while typical steppe originated products such as furs, honey, fish glue and slaves were carried by what we can call a trans-ecological transmission, from the grasslands of the north to the arable lands to the south. This does not goes to say that luxury items such as silks, jade, precious metals and rare exotics did not own their place, but these held the lesser share of the overall trade volume.

Material products were not the only thing shifted through these trans-cultural networks. Humans carry with them not only their belongings but also their thoughts, concepts, ideas and knowledge, therefore technologies and religions found their way across the Eurasian highway no less than rolls of silk or loads of barley. One of the religions that have its history tightly connected with the Silk Routs is Buddhism.

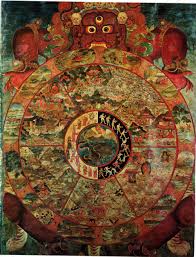

Buddhism was founded by the Sakya prince Siddhartha Gautama around the 5-6th century BC. The Buddhist path, The Dharma, emphasized the cultivation of moral and mental qualities indispensable for the Buddhist ultimate goal, the Nirvana, a state of all conceiving awareness to the true nature of things, and a consequent release from the endless chain of birth, death and rebirth.

Buddhism, starting as an integral part of the local Indic-Dharmic fabric of religions and practices, had gone through a transformation unprecedented in the Indic world; it became universal, offering a remedy for the omnipresent maladies of human existence. The Buddhist universal transformation is linked with two factors proved crucial for most of the Buddhist history, namely royal patronage, and commerce; these two factors have met their complete fulfillment during the reign of the great Mauryan emperor, third of his name, Asoka the great (r. 268–233 BC).

During Asoka’s time, the Indian subcontinent had gone through a tremendous economic growth, which brought forth a widespread support of the merchant communities and guilds in Buddhist monasteries and institutions, while in return benefiting from the hospitality services offered by the Buddhist monasteries. Asoka, a devoted Buddhist himself, converted after witnessing the absolute horrors of his own infamous Kalingan campaign, had personally supported the early Buddhist community, either by direct sponsoring, or by simple improvement of road infrastructure and safety.

With the combined movement of merchants and monks along the trade routes, Buddhism gradually struck roots in the different kingdoms and chiefdoms of central Asia. By the second century BC, It was already flourishing in Hellenistic Bactria, which produced the first anthropomorphic images of the Buddha. These masterpieces can be regarded as one of the peaks of human artistic achievements, in a graceful blend of Indic spiritual symbolism with Greek realistic naturalism.

By the first centuries before and after the Common Era, Buddhism was already well established in the then still Iranian domains of central Asia, and archeological findings confirm the Buddhist presence as west as modern Turkmenistan, deep into the Parthian territory.

On the other end of the Iranian world, Buddhism has made his first penetration in what will become the most important center of Buddhism outside of India at that time, the oasis city states of the Tarim basin, in today’s Chinese Xinjiang.

Tibetan sources date the arrival of Buddhism to Khotan to the year 84 AD, however the Tarim basin did not become a major Buddhist center until the second century, when the Han dynasty established its chain of military garrisons. The introduction of Chinese agricultural technology into the region enabled the Tarim oases to support a much larger communities then before, which in turn could host permanent religious institutes. This development enabled Buddhist monks to settle down, while constructing monasteries, temples, stupas and other establishments along the trade routes.

The most important city in the north of Tarim was Kucha, reaching its peak between the 6th and the 9th century, when it was the most populated city in the Tarim region. The city was fairly cosmopolitan at the time, inhabited by mostly Iranian, Tocharian and Indian communities. Xuan Zang, our most beloved Chinese- Buddhist- pilgrim- traveler of the 7th century described Kucha as tremendously rich and fertile city, enjoying a favorable location on the trade routes. He points out that in and around the city there are more than a hundred monasteries occupied by more than five thousand monks of the Sarvstivadan school, who “read the scriptures in origin”, Sanskrit that is.

The Sarvastivadan School is one of the earliest schools of Buddhism, belonging to a branch known as Nikaya Buddhism. Early Buddhism described life as a burden, caused by the suffering inherited in the overflowing manifestation of the different aspect of reality through the human consensuses, resulting in desire. This desire to maintain what gives us pleasure, and reject what cause us inconvenience results in pain, in suffering. It doesn’t mean that life is an unbearable torment, but that our mental interaction with the world results in ever-flowing reactions that could never give any kind of full and lasting satisfaction.

Therefore the early Buddhist movement was based on close monastic communities where its members were seeking individual salvation through meditation and a strict moral code. The Sarvastivadans and other early schools such as Mahasamagika, Dharmaguptaka and the Mulasarvastivada continued this approach but eventually disappeared or merged with later schools of Buddhist thought. The contemporary Theravada school common in Sri Lanka and South East Asian is a descendent of this monastic tradition. It is important to stress that these early school parted mostly on the basis of their monastic code, the Vinaya, rather than based on crucial dogmatic matters.

From around the second century BC, a new movement had sprouted inside the early Buddhist monasteries. This movement gradually developed literature which had stressed somewhat different aspects than earlier schools of Buddhist thought, namely the correct path for enlightenment, the nature of conciseness and additional development of the Buddhist logic tradition.

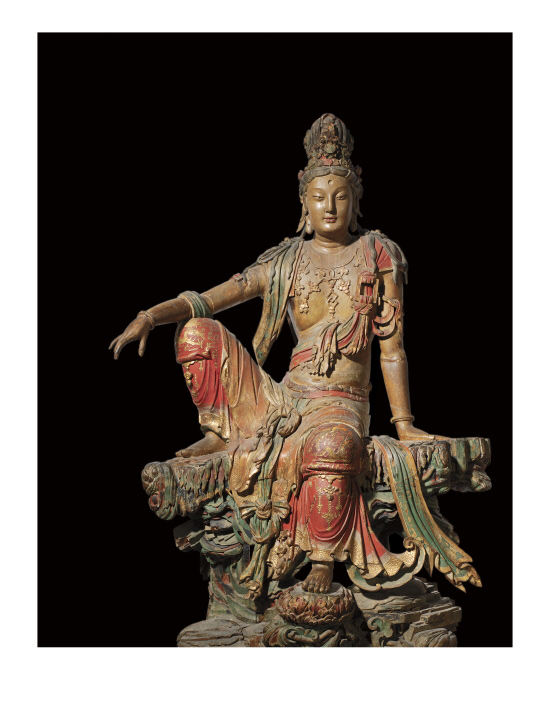

The most well-known aspect of this movement eventually dubbed as the “Mahayana”, or great vehicle , is the Bodhisattva, a being so immersed in compassion, it postpone its own achievement of full enlightenment in order to aid all sentient being to achieve the same goal.

The Mahayana movement most probably started in India itself, but continue to develop and mature far to the north, in Gandahara, Bactria and in the Tarim basin of Xinjiang, which by the second century became a major hub for Dharma teachers, translators and monks from India, Iran and china, all sitting together in monasteries in Khotan, Turfan, Kucha and other centers, translating and copying Sutras and other scriptures from various Indian and Iranian languages into Chinese, while preparing the way for the propagation of Buddhist seeds into the fertile Chinese soil.

The question of Iranian influence on early Buddhist ideas is still under debate, but it had been suggested that Mahayana concepts such as the future Buddha Maitreya and the idea of a post-life “Pure land” which gained immense popularity in the later East Asian Buddhism had come from the Iranian world. Considering the numerous monks, translators and missionaries of Iranian stock active in the formatting years of Chinese Buddhism, (One of the them, Ān Shìgāo 安世高 ,was actually a Parthian royal before heading east as a Buddhist monk) it will not be surprising, but nonetheless this influence is still questionable.

One of the important figures of this vibrant era was Kumārajīva, ( 344-413), a Kuchan monk and a translator. Kumārajīva’s early education was based on the Nikaya Sarvastivadan school, but later on in his life he inclined towards Mahayanian ideas. His colossal Chinese translational work includes Nagrajuna’s “Root verses of the middle path” (Mūlamadhyamakakārikā), a selection of “Perfection of wisdom” (Prajñāpāramitā) Sutras, such as the diamond sutra and other important Mahayana sutras, such as the Lotus, Amithaba and the Vimalakīrti Sūtra.

These details may seem trivial or even dull, but for anyone who has even the slightest interest in Buddhist culture and philosophy, it must be stressed that the Tarim basin was the gateway which made Chinese and subsequently the entire East Asian Buddhist culture even possible. Everything that tend to arouse the western appetite for Buddhist exotica, the Shao Lin monks, the impressive Tang dynasty Pagodas in Xian, and the Japanese Zen gardens and one hand clap, might have not come to being without the establishment of the Tarim basin centers of learning and translation. More than that, given the eventual extinction of Buddhism in Central Asia as well as in its Indian cradle, the Chinese translations of the Mahayana sutras are the only channel (along with the Tibetan traditions) through which these where actually preserved as a living tradition.

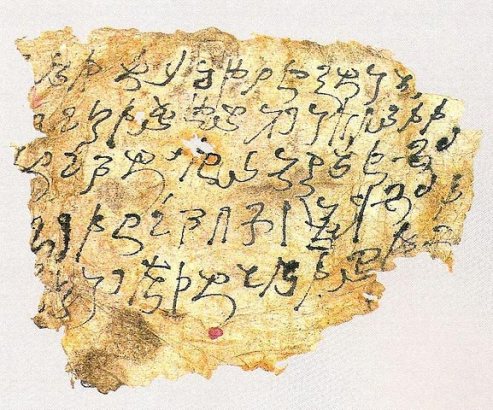

In the recent generations with the discovery of ancient manuscripts in Pakistan, Afghanistan and central Asian China, modern scholarly can now reassess the Buddhist transmission along the Silk Roads, and subsequently even to question certain choices that were made by early translators into the Chinese language, followed by our own understanding of these materials.

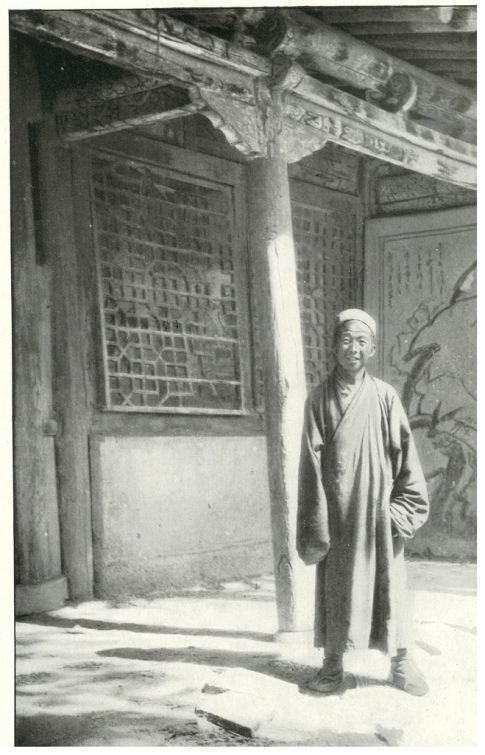

At the turn of the 19th century, a Daoist monk named Wang Yuanlu had made a discovery that will eventually be recognized as one of the most important in the history of Buddhist research.

Wang, a native of Hubei and former recruit of the Qing imperial army, has arrived at Dunhuang in the Gansu province sometime around the 1890s. Self-appointed guardian of the Buddhist Mogao grottos outside of Dunhaung, Wang has taken the task of cleaning, maintaining and “restoring” the ancient monastic complex, after decades of neglect and deteriorating.

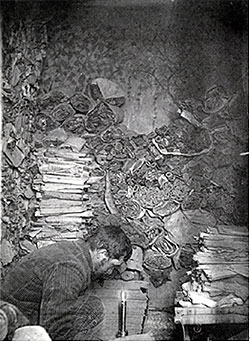

One hot 1900 summer’s day, Wang’s hired laborers were busy clearing the sand and sediments out of one of the caves when all of sudden one of them spotted a crack in one of the murals. Suggestively showing the outline of a doorway, the plastered and painted wall drew Wang`s attention and he ordered to break it down. As the cave’s wall was taken down piece by piece it reveled something that was well sealed for a millennia. It was scrolls, thousands upon thousands of scrolls.

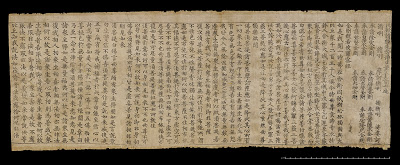

The Dunhaung scroll collection represent so well the central Asian world in which it was created. It contains manuscripts in several languages, including Chinese, Tibetan, Sanskrit, old Uyghur, Sogdian, Khotanese and even Hebrew. The content of those scrolls revolves around anything from Buddhist Sutras to Tibetan administrative reports, Daoist commentaries on the Dao de jing and religious scriptures of the now extinct Nestorian Christianity and the dualistic Manichean faith. One Buddhist sutra was even touchingly dedicated to a deceased ox by its loving owner, imploring it will not again be reincarnated into an animal form, suffering under human hands.

The most celebrated specimen of the Dunhuang collection is probably the 868 AD Diamond (Vajracchedikā ) Sutra , translated by our very own Xuan zang, and what is the earliest known printed text, press copied centuries before Gutenberg even laid his hand on a block print letter. The printed scroll, composed out of five sections, was most probably copied as an act of merit. In Buddhist tradition the coping and distributing of a Sutra, an embodiment of the Buddha itself is considered a blissful act, which benefits the scribe as well as the person who commissioned it with unmeasurable Karmatic advantage. In fact, many of the painted grottos themselves are an outcome of vast donations made by groups, individuals and entire families, many of them traders, giving alms to the local monastic community, while contributing to their Karmatic balance as well as to the Buddhist artistic legacy on the way. This patronage system reaffirms the direct connection between trade and the spread of Buddhism and its ability to thrive in the Central Asian network of desolated oases.

As such, this collection is indispensable for our understanding of many fascinating matters such as the Tibetan early imperial history, the Sogdian vast Eurasian trade network and most of all, the manner through which Buddhism was transmitted overland from India, trough greater Iran and eastwards into China proper, while reveling some of this important link between China and a now a completely lost world of the Central Asian Buddhism.

As we know today, Wang’s “library cave” was sealed sometime around the late 11th century, why it was sealed no one knows for sure. A claim was made that the manuscripts were hidden in the face of an upcoming Muslim invasion. Other theory suggests the texts were fallen out of use, and sealed away due to their sanctity, not much unlike the famous Jewish Geniza of Cairo. After the cave was discovered, Wang’s hoard of manuscript laid in the dark for some years, while the Chinese authorities repeatedly refuse to pay it the appropriate attention. Eventually the word of the hidden stash reached the ears of several western explorers, researches, treasure hunters, and all of these combined. At that time, clues of mysterious lost Buddhist kingdoms lying silently in the sands under the Muslim upper-layers of Central Asia had captured the western imaginations and dispatched rival expeditionary missions, British, Germans, French and Japanese all racing for fame, glory and knowledge.

Eventually the first to reach the caves and obtaining the lion’s share of the catch was the British-Hungarian Jewish explorer, Sir Aurel Stein. Stein and his faithful Turki (what we call today Uyghurs) crew accompanied by Stein’s legendary fox terrier, Dash II, managed to persuade Wang to sell a large portion of the collection, that was sent to London along with other manuscripts and artifacts from Khotan, Miran and other lost stronghold of the Dharma.

Following Stein others came, buying off most of what’s left of Wang’s manuscripts and striping, sometimes brutally removing some of the more exquisite murals of Dunhunag, Kizil, Bezeklik and other Buddhist grottos of the eastern Silk Road. Some of the finest of them where sent to Berlin by the a German expedition where they have been permanently attached to the museum wall, only to be completely destroyed by the allied forces bombardment of the German capital during the second world war.

The Modern Chinese approach to these western expeditions see them as no more than tomb raiders and thieves, clawing at Chinese historical heritage under the twilights of the crumbling Qing dynasty. Despite the fact that these early archeological expeditions were indeed inseparable from the European colonial legacy, and were part of an open arms race to fill up Europe’s museums with artifacts, considered western property by divine providence itself, the question what would have happened to the Dunhuang collection if it was to stay in China remains open. Given the international recognition the scrolls of Dunhuang received while been preserved, studied and recently digitalized and uploaded online, and on the other-hand the sheer distraction of Chinese historical heritage during the upheavals of the Chinese civil war and especially during the ridiculously destructive “Cultural revolution” , we can only assume the fate of this irreplaceable collection if had not been taken to the west.

Either way, the information gathered from textual and archeological findings, from Xinjiang and Gansu as well as from other central Asian locations in Pakistan, Afghanistan and Transoxania, enable us to reconstruct a long lost world of flourishing Buddhist monastic and lay communities. These communities were firmly connected to the Central Asian and Iranian cultural worlds, and its members wrote Sutras and commentaries in their own native tongues while imbedding their own imprints on a then living Buddhist culture. Perhaps future research will allow us more understanding of this lost world of Central Asian Buddhism.